About mobility degradation in MOSFETs, and the carrier velocity saturation model.

Effect of Gate Voltage on Carrier Motion

The previous given equations to calculate

Electrons moving in the channel are under the influence of two electric fields: the vertical field from the gate, attracting it to move vertically towards the gate oxide, and lateral field from the drain, attracting it to move laterally towards the drain.

The electron will bounce off the silicon and oxide interface a few times before reaching the drain. If the vertical field is strong, electrons will bounce more times off the surface. The collision between the electron and the interface is inelastic, causing energy loss and reducing the velocity of the electron. Therefore, it will take longer time for electrons to reach the drain.

Thus, the mobility

To correct for this effect,

The Effective Vertical Electric Field

To quantify the variation of

Electrons at different distance from the interface will experience different vertical electric field. To simplify the problem, the average electric field is used, assuming it to be the electric field experienced by all electrons.

- The average vertical electric field is

- An intuitive derivation of this equation:

- The average electric field can be considered the electric field experienced by an average electron

- The average electron is the one with half of the electrons in the channel above it, and half below it

- The electric field starts at a positive charge at the game, and terminates at a negative charge at the substrate

- Electric field terminating above the average electron will not be experienced by the average electron

- Therefore, only the electric field terminating below the average electron will be experienced by the average electron

- Once the charge

- The charge

- Half of the inversion charge

- The entire depletion charge

- Half of the inversion charge

- Thus the equation is obtained

- We need to further express

- The inversion charge density is

- The depletion charge can be calculated with the following equation

- The effective vertical electric field can now be expressed as

- Once

- The inversion charge density is

Calculating Effective Mobility

We still need to obtain the relation between

There are many theories predicting the effective mobility based on the microscopic effects, but none of them fit the experimental data well.

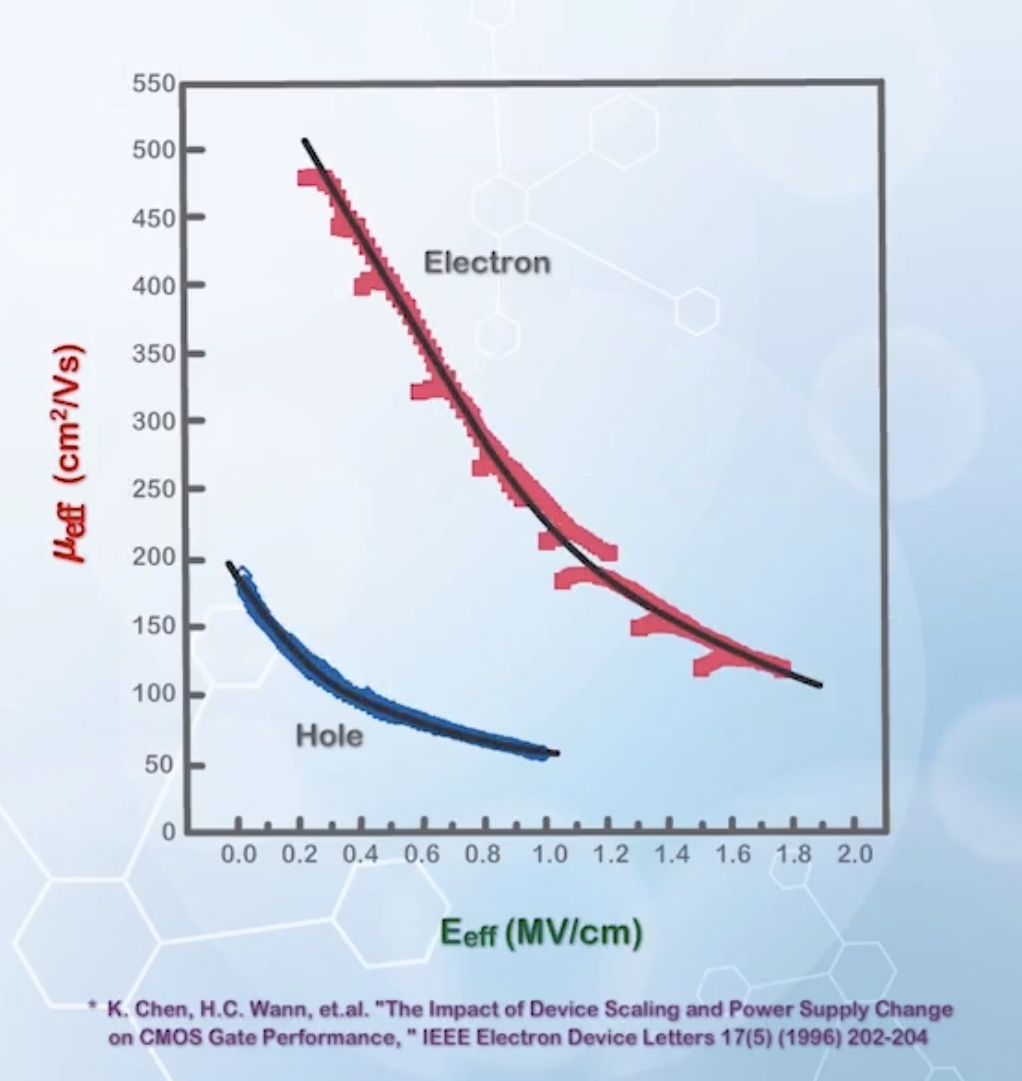

In practice, engineers rely on experimental calibration to obtain the effective mobility. Experimental data are collected are plotted:

Regardless of the gate oxide thickness and the substrate doping concentrations, they all fall onto a single curve.

As the results are very consistent, an empirical equation is more practical to use, rather than complex theoretical models.

The empirical equation is given as

and a widely used set of parameters for this model is

| Electrons | Holes | |

|---|---|---|

Some other sets of parameters are also used, due to variations in the fabrication process and the physical structure.

This is the universal mobility model, as it can fit different sets of data very well.

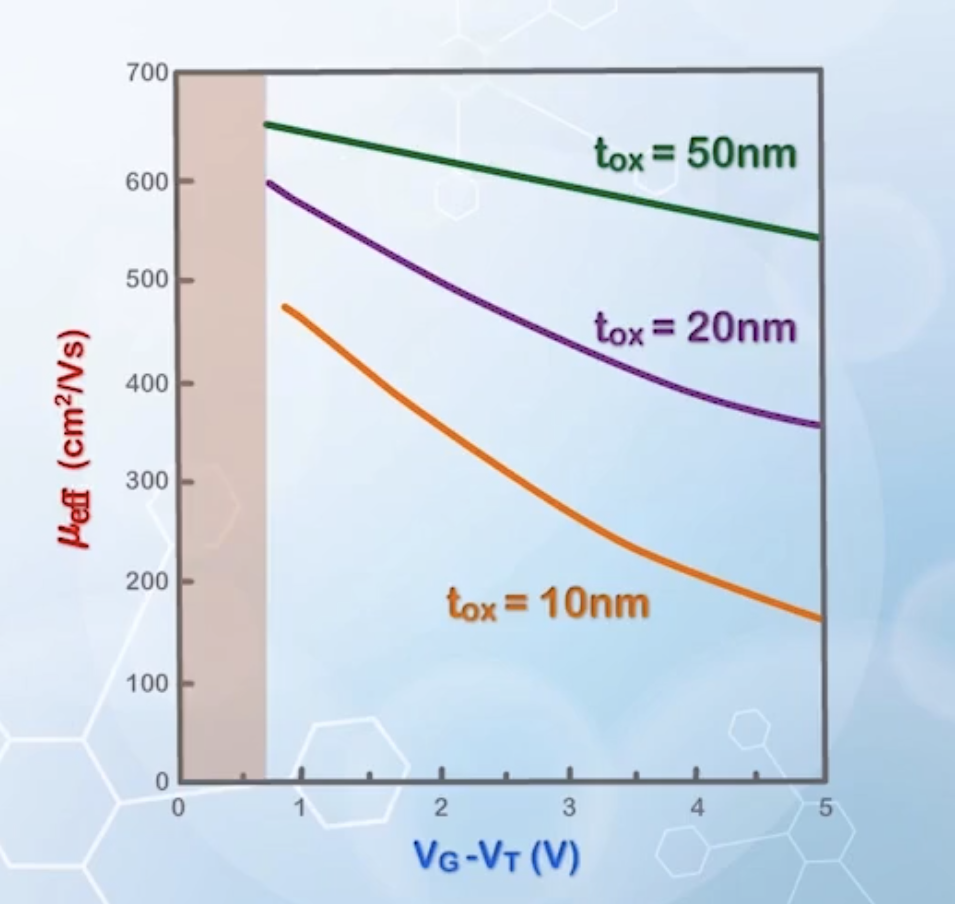

The relationship between

Now we can plot

Note that the model may not be accurate for

From the graph, we can see that when

thinner oxide thickness will lead to larger

Therefore, the mobility degradation effect may not be important for older MOSFETs with thick oxide, but it is very important for modern MOSFETs with thin oxide.

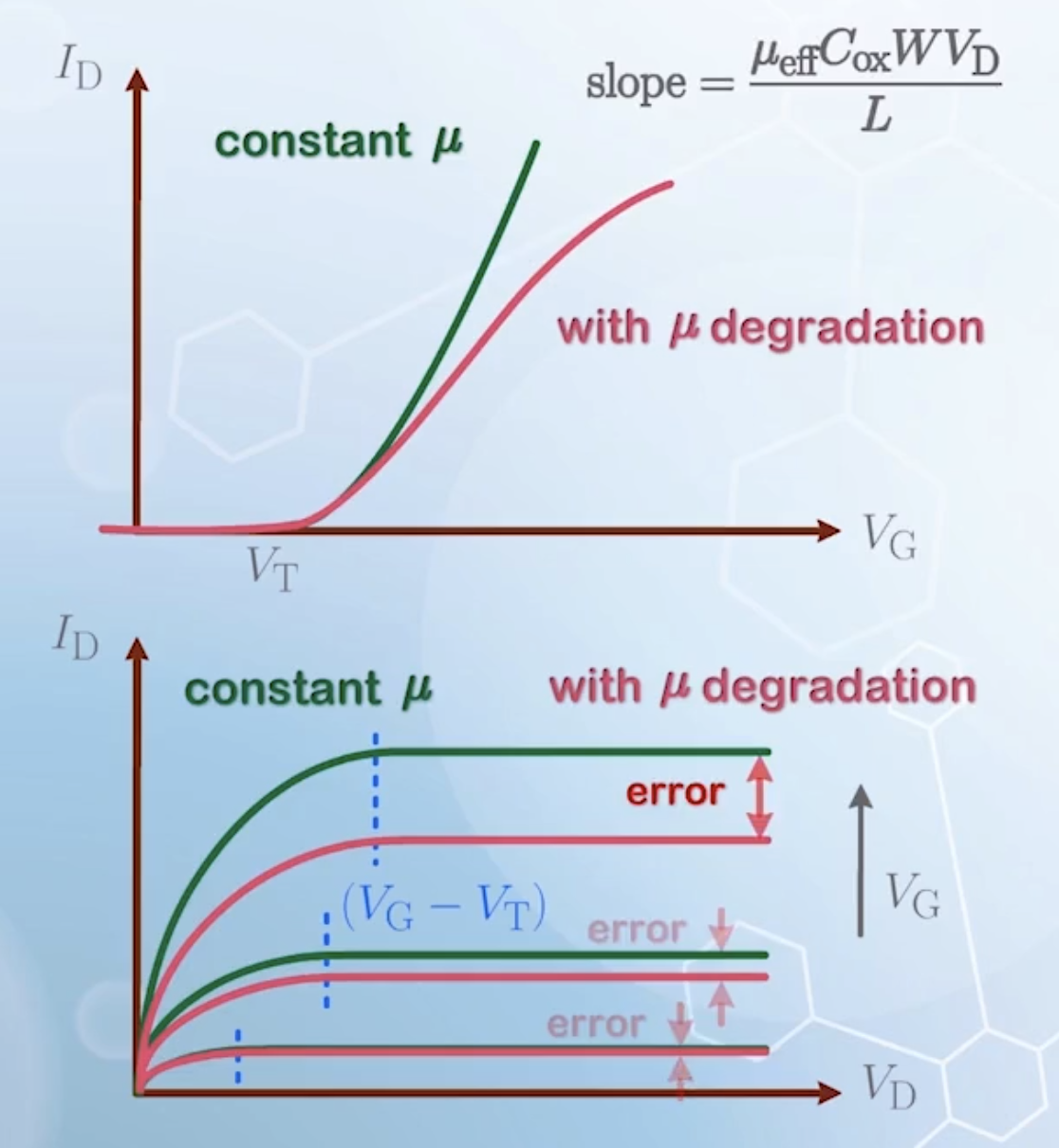

The

Compared to constant

Carrier Velocity Saturation Model

Up to now, we have linearly related the carrier velocity

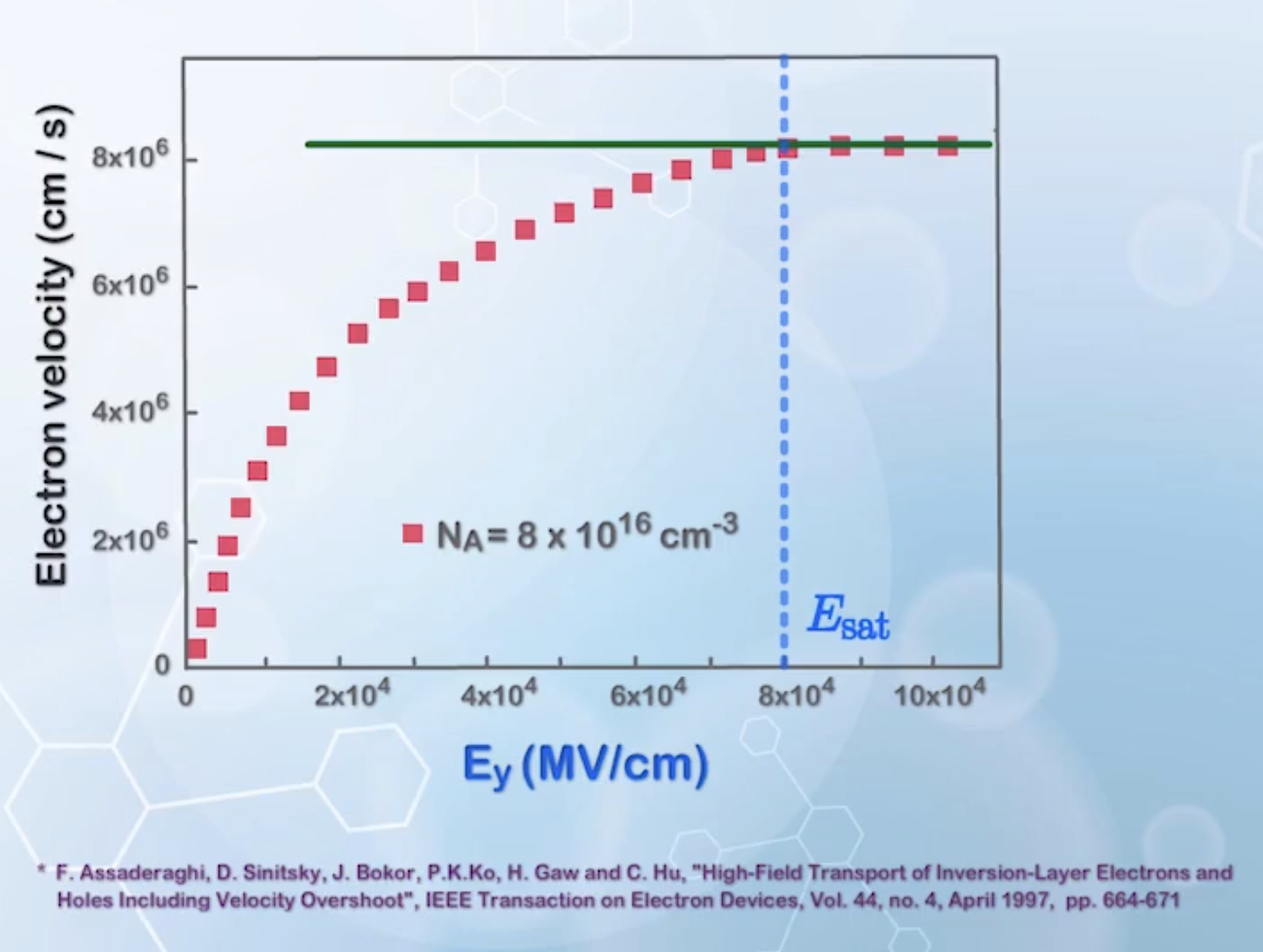

From measurements, carrier velocity saturates at a certain electric field

To include this effect in drain current calculation, we need to derive a new expression for carrier velocity

The easiest way is to use a straight line to connect the two known points: (0,0) and

To be more accurate, the slope of the curve, or mobility, should decrease when the lateral electric field increases, so a better expression would be

The slope will be decreasing with increasing

providing better fitting for the data.

We have the measured

where

To derive the new drain current equation considering velocity saturation

Compared to the classical model, there is just an additional factor of

As for the saturation region, we define

Carrier Velocity Saturation v.s. Pinchoff

Comparing the two set of equations

- The pinchoff model

- The carrier velocity saturation model

- In the linear region, the two models are very similar, with just an additional factor in the carrier velocity saturation model that reduces the increase in

- The new

- Carrier velocity saturation will kick in before pinchoff occurs, preventing pinchoff from happening

- This is because the carrier velocity saturation limits the maximum carrier velocity, preventing the carrier density from reaching zero at the drain end, as

- This removes the inconsistency in the pinchoff model that requires infinite carrier velocity

The problem of the pinchoff model is that it does not provide a clear physical image for the ending of the gradual channel region, and we arbitrarily picked

By providing a more physical definition for the end of the gradual channel region, the carrier velocity saturation model avoids reaching the pinchoff condition, and thus solved the problem.

Also, the saturation current in the carrier velocity saturation model is also physically derived, instead of extending the flat portion of the linear region equation of the drain current, and

The same substrate charge factor